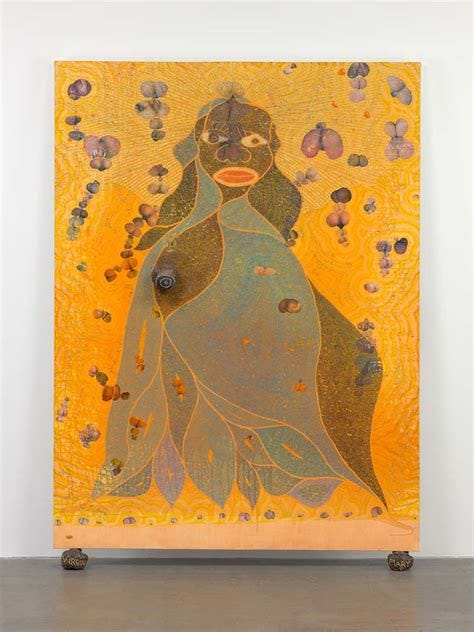

One of my favourite works of art is Chris Ofili’s ‘The Holy Virgin Mary’, and I’ve been thinking about it a lot recently, for reasons unbeknownst to me. Chris Ofili, a British-Nigerian artist that comically questions racial and sexual stereotypes, is pretty infamous in the art world for using… ‘unconventional’ materials in his pieces.

‘The Holy Virgin Mary’ is an 8-foot tall piece depicting Mary as a stylised black woman, and includes cut-outs from pornographic magazines and elephant dung. It’s quite a controversial piece, and caused a huge scandal when it first came to the Brooklyn Museum in 1999, as the mayor of NYC at the time, Rudolph Guiliani, tried to evict the museum for showing it, and one person tried to deface it with white paint, so it definitely caused quite an uproar (Abrams, 2006).

So why is it that so many people were so upset about this painting? I believe that the only problem that people have with this Madonna figure is that she is Black, but I’ll examine some of the criticisms typically given. First, some, including Guiliani, believed it to be an attack both on the Virgin Mary and on religion as a whole itself, stating that smearing elephant dung on the image of a religious symbol was a “deeply offensive" act, bereft of any social or artistic value” (Davies and Fenton, 1999). However, Ofili himself is Roman Catholic and used to be an altar boy, and the dung isn’t smeared on in a defacing manner, but rather one lacquered piece is placed to represent a bare breast, and two others hold the canvas up.

There is a belief that the painting is a crude and disrespectful portrayal of the Virgin Mary, but I don’t believe this to be true. On the contrary, Ofili uses a lot of the typical iconography, what is referred to as the canon of representation, used in the portrayals of the Virgin Mary. These include:

The background of the piece being a glittered gold, paying homage to the traditional gold backgrounds of a lot of religious paintings, especially those of Mary, inspired by the Byzantine era, as it evokes ideas of holiness and transcendence (Hubbard, 2021).

The gold lines that emanate from Mary’s head are reminiscent of a halo, drawing attention to and reinforcing her divinity.

Mary wears her ubiquitous flowing blue cloak, which symbolises her purity; divinity; and royalty (Fuchs, 2015).

Mary has her dress open, showing a breast as is often the case in traditional representations, which was often a reference to her fertility and femininity.

All of these elements fall in line with her traditional canon of representation, so how exactly is it disrespectful then? For a comparison, here is an example of a more traditional representation (title and artist unknown) that, with the exception of the bared breast, exemplifies all of these rules:

Some state that the problem with ‘The Holy Virgin Mary’ is its “sexual” nature, but is that necessarily true? We have already seen that a bared breast is part of the canon of representation of the Virgin Mary, and is a part of probably a majority of work in which she is depicted. Perhaps one could point to the pornographic images surrounding Mary, but Ofili adds these in a callback to the putti, or cherubs, typically pictured in many religious and secular artworks, which typically represented profane passion and erotic love. I see this choice rather as finding a modern, albeit crass, image to portray the same message, furthering my earlier point about the employment of Mary’s canon of representation.

Why then, is this Mary more sexually explicit and more disgusting than her predecessors? Is it because, and I’m sure you’ve *never* heard this take before, but is it because maybe perhaps Black women are historically and socially viewed as more sexual and erotic, and therefore more dangerous and depraved for this perceived eroticism, than white ones? Well, yes! Racism once again rears its ugly head in the art world, which is surprising to no one. Ofili intentionally chooses to make Mary Black, and he exaggerates it by giving his virgin Mother unrealistic and distorted facial features, embracing racial stereotypes about sexuality and blackness: that Black women are hyper-sexual figures (Hubbard, 2021). Ofili not only accepts that Mary’s blackness and her stereotypically Black features are made to be inherently over-sexual, but plays on this by ‘patterning’ the image with overtly sexual pornographic cutouts of Black women.

Ofili uses this painting to expose the hypocrisy of Western art and to critique the whitewashing of religious figures as a form of white supremacy: if authoritative and ‘good’ figures like Mary and Jesus are white, then authority and goodness are white (McFarlan, 2020). What Ofili exposes in ‘The Holy Virgin Mary’ is that whiteness is put on a pedestal, and it is a grave offence to suggest anything counter to this belief, regardless of how historically accurate or politically important it is, as it threatens the upholding of white supremacy in religious spaces and especially in the art world.

Sources:

Fuchs, Margie. “Mary and the Colors of Motherhood”. National Museum of Women in the Arts, 20 February 2015, nmwa.org/blog/nmwa-exhibitions/mary-and-the-colors-of-motherhood/#:~:text=Here%2C%20Mary%20wears%20her%20signature,was%20associated%20with%20Byzantine%20royalty.

Hubbard, Sue. “Chris Ofili: The Holy Virgin Mary – Significant Works”. Artlyst, 29 September 2021, artlyst.com/features/chris-ofili-the-holy-virgin-mary-significant-works-sue-hubbard/.

McFarlan, Emily. “How an iconic painting of Jesus as a white man was distributed around the world”. The Washington Post, 25 June 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2020/06/25/how-an-iconic-painting-jesus-white-man-was-distributed-around-world/.

Speaking Freely: Trials of the First Amendment, Floyd Abrams, Penguin, 2006, ISBN 0-14-303675-0, pp. 188–230

Whiff of sensation hits New York (archive.org)